The first post in this series can be found here.

A common explanation of 1 John is that John gives tests to determine whether a person is a believer or not. We tell Christians struggling with faith to read 1 John to see what it says about them. Do they pass the tests? I cited John MacArthur in the Introduction as a popular proponent of this perspective.

Unfortunately, this understanding can do more harm than good, potentially most clearly seen in 1 John 2:12–14. This is because of a common misinterpretation represented in translation. Most versions use the word “because” six times in this text. If you read my translation below, you will see six colons (:) instead.

I explain this in the exegesis that follows, but if John wrote “because your sins have been forgiven,” then I cannot know this book applies to me if I am struggling to believe he forgave me. It subverts the whole enterprise of viewing 1 John as tests. This is exacerbated by the reality that the previous two sections of 1 John have created a dichotomy between true and false believers, those John counts as insiders and those John labels outsiders.

Careful readers are probably worried about their position by the time they get through 2:11. And this is why John writes what he does in 2:12–14.

1 John 2:12–14

12I am writing to you, little children1: Your2 sins have been forgiven through his name.

13I am writing to you, fathers: You have known the one from the beginning.

I am writing to you, young men: You have prevailed over the3 evil one.

14I wrote4 to you, children: You have known the father.

I wrote to you, fathers: You have known the one5 from the beginning.

I wrote to you, young men: You are strong, and the word of God6 remains in you, and you have prevailed over the evil one.

The footnotes above discuss textual variants. The bold numbers are verse numbers.

Jump menu

Exposition and Application

Saint Augustine Assessment

Gospel Plea

Great Commandment Plea

Reflection Questions

Exegetical details

The prior two sections of 1 John have emphasized verbal claims (“If we say” [1:6, 8, 10]; “the one who says” [2:4, 9]) and the alternative actions (1:7, 9; 2:5, 6, 10). This has the effect of demonstrating the conclusion John will reach in 1 John 3:18—actions speak louder than words.

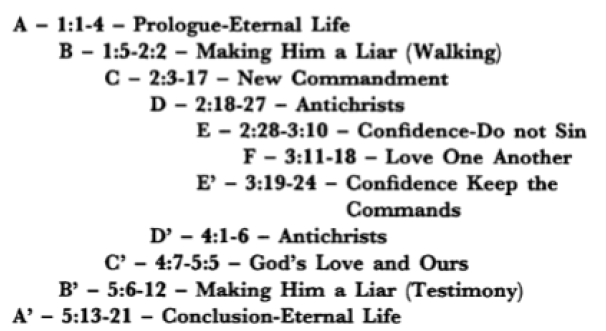

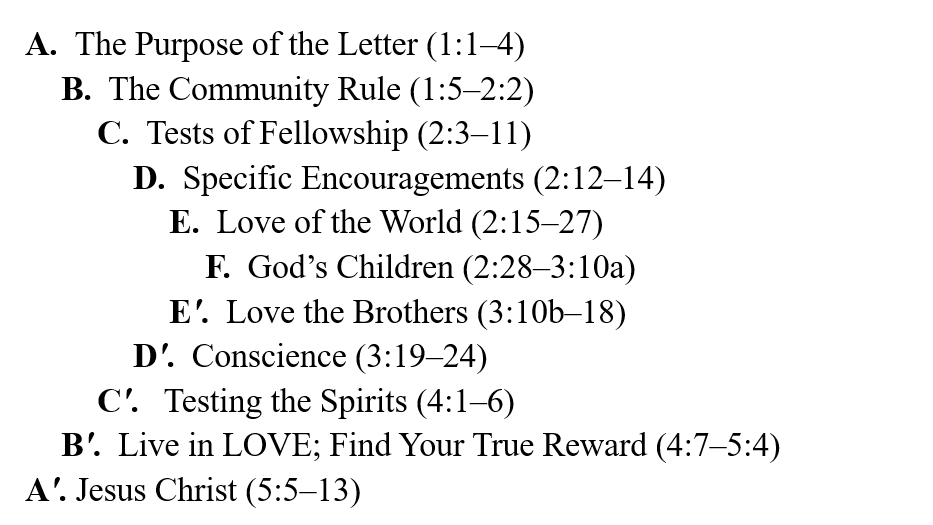

It also supports my decision to break from Thomas’ chiastic outline at this point. The difference began when I cut the last entry at 2:11 and summarized the section as “Tests of Fellowship.” Thomas takes 2:3–17 together and calls it the “New Commandment.” For Thomas, 2:3–17 corresponds with 4:7–5:5 (“God’s Love and Ours”). This makes sense, but 2:12–14 has little explicitly to do with the “New Commandment,” though, as this exegesis will demonstrate, it greatly reflects the “New Covenant.”

In my chiastic outline, 2:3–11 (“Tests of Fellowship”) corresponds with 4:1–6 (“Testing the Spirits”). John’s inclusion of 2:12–14 has puzzled interpreters, leading them to ask how it fits in the argument of the book.8 If 2:12–14 is separated from 2:3–17,9 then it interestingly corresponds with 3:19–24 (“Conscience”). This leads 2:15–27 (“Love of the World”) to correspond with 3:10b–18 (“Love the Brothers”). This (3:11–18) is the text that Thomas posits as the primary point of 1 John.

But in my outline, 2:28–3:10a becomes the centerpiece. This section focuses on “God’s children.” Calling people to love and obey is worthless if they do not understand their identity. This is why 2:12–14 exists. It reiterates John’s readers’ identity. And when we note that the corresponding passage (3:19–24) is dependent on the previous verse to make sense of a pronoun (“this”), it reiterates that we act from our identity.

So in 1 John 2:12–14, John reassures his readers of the realities of their faith so that they are empowered to obey the injunctives that follow in the rest of the book.

There are three primary interpretive questions in this text. First, who are the children, fathers, and young men? I will offer an answer after working through the text as it stands. (I will follow that discussion by explaining the apparent lack of women in this text.) Second, how are we to understand the ὅτι in this text? I will discuss this when we get to the first instance in the text. Third, why does the verb tense of γράφω change from a present to an aorist in the second half of the text? I will look at this when we get to the aorist section (v. 14).

12. I am writing to you, little children: Your sins have been forgiven through his name (Γράφω ὑμῖν, τεκνία ὅτι ἀφέωνται ὑμῖν αἱ ἁμαρτίαι διὰ τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ). John refers to the first group he is writing to as τεκνία (little children). This is a Johannine exclusive word, occurring only seven times (John 13:33; 1 John 2:1, 12, 28; 3:18; 4:4; 5:21) in the NT. The fact this word occurred previously in 1 John 2:1 implies it somehow refers to the entire group John is addressing (we will return to this idea at the end of this section).

The word following τεκνία in Greek is ὅτι, which can either be translated “that” or “because.” So, is John writing because their sins have been forgiven, or is he declaring that their sins have been forgiven? And it is a question many do not see as important: “The original readers may not have pressed any sharp distinction between the two uses of the conjunction, a distinction that is forced on us by having to choose one of two different English words.”10 My own translation hints at this perspective by relegating the ὅτι to a colon. However, if we look at the most commonly cited purpose clause in 1 John (5:13), we see that one of the primary purposes John had for writing was that his readers know they have eternal life.11 By telling the “little children” their sins have been forgiven, he is doing two things. First, he is reiterating their status: possessors of eternal life. Second, he is reassuring them that they are not included in the group making empty claims that he previously called out in 1:5–2:2 and 2:3–11.12

This understanding moves the argument forward. If John were using ὅτι causally here, it would justify the claim that this text “sits awkwardly within the letter” and “break[s] the letter’s flow.”13 But if it is a reassurance, it makes good sense to come immediately after the salvos launched in the previous two sections.

And what is John reiterating to his readers? He says, “Your sins have been forgiven through his name.” This connects back to the promise of 1 John 1:9, but here John applies it to his readers. This would imply that they have confessed their sins.14 They are not claiming to be without sin. They know they have a need, and they know the only place where their need can be met. As Augustine said, “Your sins are forgiven through his name, not through anyone else’s.”15

13. I am writing to you, fathers: You have known the one from the beginning (γράφω ὑμῖν, πατέρες ὅτι ἐγνώκατε τὸν ἀπʼ ἀρχῆς). The second group John is writing to is the πατέρες (fathers). This is the only place in 1 John where πατέρες is used to refer to anyone other than God.16

John reassures this group that they “have known the one from the beginning.” This is a direct reference back to 1:1 and 2:7. As such, it refers to Jesus.17 This language matches the wording in 2:4. John is continuing to reassure his readers on the basis of the doubts that might have entered their minds from 1:5–2:11. Whereas some claim to know Christ, this group truly knows Jesus.

I am writing to you, young men: You have prevailed over the evil one (γράφω ὑμῖν, νεανίσκοι ὅτι νενικήκατε τὸν πονηρόν). The third group John is writing to is the νεανίσκοι (young men). This is the only place (and 2:14) this word occurs in 1 John. Some examples of νεανίσκοι in other parts of the New Testament are the “rich, young ruler” in Matthew 19:16–22;18 the one who fled naked from the garden when Jesus was arrested in Mark 14:51; the widow’s son who Jesus resurrects in Luke 7:14; and Paul’s nephew in Acts 23:16–18. Philo categorized νεανίσκοι as anywhere from 21 to 28 years old.19

John tells this group that they “have prevailed over the evil one.” This is the first mention of “evil one” in 1 John, though we will see him again in 3:12 and 5:18–19. I purposefully say him. This is the devil.20 Lieu notes, “The choice of epithet takes the focus away from a strange figure, neither human nor divine, who inhabits the world of story and vision, and fixes it instead on the moral dimension.”21 John reassures this group that they have victory—not over a spiritual entity—but over their own propensities to immorality. Immorality being primarily understood as a lack of love.

14. I wrote to you, children: You have known the Father (ἔγραψα ὑμῖν, παιδία ὅτι ἐγνώκατε τὸν πατέρα). John switches verb tenses here. Whereas the prior two verses were in the present (“I am writing to you”), this verse switches it to the past tense (aorist): “I wrote to you.” Why the change?

Some would appeal to a previous writing, like 2 or 3 John, but this need not be the answer.22 Lieu explains, “It is standard in Greek letters to use both the present, ‘I am writing,’ reflecting the author’s standpoint, and the past ‘I have written,’ reflecting the readers’ standpoint (cf. 2:1 and 5:13).”23 As her example texts highlight, 2:1 comes first and is present, and 5:13 comes later and is aorist. Schnackenburg highlights several other examples of the aorist, ἔγραψα, referring to the letter itself: 1 Corinthians 5:11; Galatians 6:11; Philemon 19, 21; 1 John 2:21. He also notes that secular letters use the word similarly.24 Bultmann correctly explains the aorist as “stylistic variation.”25

John is repeating himself here for emphasis. In a culture where letters were written to be read aloud, this is how John bolds, italicizes, and underlines the importance of this point.

The people he is addressing first in this verse are referred to as “children” (παιδία). Philo classes this age group as less than 7 years old.26 Some would differentiate this group from the first group introduced in 2:12, since the word there was τεκνία, but this seems less than accurate.27 For instance, Marg Mowczko offers the distinction between “all believers” (τεκνία) and “new believers” (παιδία),28 and Westcott notes a distinction between “kinsmanship” (τεκνία) and “subordination” (παιδία).29 The only thing that might suggest παιδία here belongs to a different category than τεκνία in 2:12 is the repetition of παιδία in 2:18 (the only other use of this word in 1 John).

Is John here referring to all his readers, or only a certain subgroup? Brown notes that understanding John’s intention as 3-categories in 2:12–14 is less than sensible since it would go children, elders, young men—not a chronological age progression.30

What John says here is different from what he said of this group in 2:12. There he specified that “your sins have been forgiven through his name.” Here he says, “you have known the father.” While one could argue—see prior paragraph—that the differences here are related to the different word of address in each verse, I would argue that John purposefully used a different word of address in each because his reason differed in each. But if we look closely, we will see that this is still the same group. Given that this text comes immediately after 2:3–11, and given that one key point John addressed there was claims to know God (see 2:3–5), it makes sense that he would encourage his readers simultaneously that 1) yes, they know God, and 2) their sins have been forgiven. In 2:3, John said they can know they know God if they obey his commands. Forgiveness is necessary since no one perfectly obeys his commands (1 John 1:8–10).

I wrote to you, fathers: You have known the one from the beginning (ἔγραψα ὑμῖν, πατέρες ὅτι ἐγνώκατε τὸν ἀπʼ ἀρχῆς). The only difference between this phrase and 2:13a is the aorist ἔγραψα here. As this was discussed above, it will not be rehashed here. John wants to emphasize that the fathers have known Jesus and all he entails (see 1:1–3). As Bultmann notes, τὸν ἀπʼ ἀρχῆς “can certainly not be the πατηρ (‘father’) of v 14a.”31

I wrote to you, young men: You are strong (ἔγραψα ὑμῖν, νεανίσκοι ὅτι ἰσχυροί ἐστε). John again uses the aorist, emphasizing what is true of the young men. And by way of variation, he inserts two clauses between “young men” and “you have prevailed over the evil one.” First, he reassures this group that they are strong. This is the only time John uses ἰσχυρός outside of Revelation.32 It is possible, as Jobes notes, that there is an allusion here to the physical stature of young men in Greek culture; she notes that the word was used “in Greek literature to describe the stage of a man’s life when his growth was completed and he was in his prime strength.”33 Bultmann argues, rightly, that this should be understood as spiritual strength. He connects it to the following clause.34

And the word of God remains in you (καὶ ὁ λόγος τοῦ θεοῦ ἐν ὑμῖν μένει). Bultmann writes, “The strength of the ‘young men’ rests on the fact that God’s word ‘abides’ in them and determines their existence.”35 Brown further clarifies the identity of ὁ λόγος τοῦ θεοῦ (“the word of God”), writing:

The “word” here is not the personified Logos of the [Gospel of John] Prologue but “the word of life” or divine message revealed by and in Jesus (1 John 1:1) or, even more precisely, the word (or commandment) of loving one’s brother, stressed in 2:5–11. The connection of the “Young” to commandments was already made in the OT: “How can a young man [neōteros] keep his way pure? By guarding it according to Your words [logos]” (Ps 119:9).36

Bultmann connects forgiveness to the word of God, noting, “In a certain sense the gift of forgiveness belongs also to the “commandments,” insofar as it demands from man the admission of his nothingness.”37

John is playing off the fact that literal young men are often physically strong, and similarly—by virtue of confession, forgiveness, and obedience—his readers have spiritual vitality from the word of God (the “word of life” in 1:1).

And you have prevailed over the evil one (καὶ νενικήκατε τὸν πονηρόν). Previously, John jumped straight to this phrase. Now he has explained the background for it. The reason why this group prevailed over the evil one is not due to their own strength, but due to the strength infused into them by the word of God.

This does not mean “Read the Bible to be spiritually strong,” but it also does not mean the opposite. Scripture reading is important.38 It is the only way we will ever know Christ and his work and words “from the beginning.” But that is John’s point. In order to be spiritually strong, our Scriptural hermeneutic must be Jesus.39 And Jesus did not just know right theology; he acted rightly. When I previously cited Lieu that the point of mentioning “the evil one” was to fix our gaze on the moral dimension instead of an ethereal enemy,40 this was why. But we will dive more into this reality later (see 4:17).

How are we to understand these age groups? Based on everything discussed so far, John mentions three different age groups: little children (τεκνία and παιδία), fathers (πατέρες), and young men (νεανίσκοι). One argument against these referring to three distinct age groups in John’s church is the lack of chronology. Why does John list “young men” last if “young men” would be the stage between “children” and “fathers”?41 For this reason, John probably did not have three specific groups in mind. But are there two?

Many would understand “little children” as referring to the whole group and then subdividing the whole group between older (fathers) and younger (young men).42 Brown called this “the most popular view among modern scholars” in 1982.43 But this leads to questions about gender: Does John only care about males in his subdivision? Are there even any women in this community? (See discussion below, though here it should be stated that these questions remain no matter what we say about age groups.) One of Brown’s primary supports for this view is connecting fathers and young men to different groups described in the early church and prophesied in the Old Testament. He notes Acts 2:17 (which cites Joel 2:28) and Jeremiah 31:34.44

Unfortunately, there are two problems with Brown’s explanation. First, he somewhere in his discussion sneaks away from “fathers” and exchanges it for “elders” (presbuteroi). It then becomes a discussion of church offices instead of members of John’s community.45

Second, Brown misreads a blatant figure of speech as something literal. This figure of speech is called a merism, and it is quite common in Scripture: “The most common type of merism cites the poles of a list to suggest everything in between.”46 When Jeremiah 31:34 says “all of them will know me, from the least to the greatest,” and when Joel 2:28 refers to “young men” and “old men,” the point is “everyone—irrespective of age.”47

This is why Smalley can write, “There is no obvious reason why each of the qualities mentioned should not be typical of all Christians, and not just of one group at a particular stage of spiritual growth.”48 It is not as though spiritual “fathers” no longer need forgiveness or do not know the Father. It is not as though spiritual “young people” do not know the one from the beginning. It is not as though spiritual “children” do not have victory over the evil one.49 Lieu writes, “These are not offices or fixed roles but serve to invite the community to look at itself as combining complementary strengths and insights.”50

Much like the New Commandment is the basis for John’s community, so the New Covenant is the basis for the New Commandment.51 All are included and all are on a similar playing field as it relates to knowledge, forgiveness, and victory. But this naturally raises a question.

Why are there no women mentioned?

If John is referring to the New Covenant, why does he exchange “old men” in favor of “fathers”? I think—admittedly, I have not read this anywhere else—John is making a play on words between knowing the Father and being a father of the faith.52

It is reminiscent of Jesus’ words in Luke 6:40. “A disciple is not greater than his teacher, but everyone, when they have been fully trained, will be like their teacher.” The children—all of John’s readers—know the Father, so if they press on in faith they will eventually be like the Father in everything as well.53 And this would also help explain why John uses masculine categories in this text. It is dependent on the idea, pervasive in scripture, that God is Father.54

John is not opposed to women, and he did not create an all-male community. Lieu explains the culture of the time: “Greek divisions of the ‘ages of man’ were not interested in women since they would not grow up to play their part in the life of the city.”55 John was fully submerged in this culture and naturally reflected it in his writing; the women in his audience were similarly submerged in this culture and likely did not think twice about this male-centered language.

Brown offers a grammatical argument for women being included: “Frequently in NT Greek a plural masculine noun covers subjects of both genders.”56 Unfortunately, he supplies no examples. It is certainly true in the case of ἄνθρωπος (man) and even ἀδελφὸς (brother),57 but is it true across the board? Can νεανίσκοι (young men) refer to “young people”? What about πατέρες (fathers)?

Mowczko writes, “Most Greek lexicons acknowledge that pateres can mean ‘parents.’”58 BDAG cites Hebrews 11:23 as proof that οἱ πατέρες (literally: the fathers) can refer to “male and female together as parents.”59 However, one must wonder—on the basis of BDAG’s explanation—if the plural article is required to make it inclusive—the article is missing in 1 John 2:12–14. However, despite questions on “young men” and “fathers,” it is certain that τεκνία and παιδία do not specify gender and include women as well.60

So the categories are metaphorical, inclusive of the whole congregation, whether male or female, young or old.61 Strecker goes a step farther and says, “It includes all Christians who will permit themselves to be addressed by this homily.”62 Brown argues that John’s community did not devalue women, even though women are not explicitly mentioned in 1 John; if anything, his community especially elevated them.63

In the New Covenant community that John describes, everyone matters. Love must be shown to all. All are encouraged and expected to grow on this pilgrimage.64 One day we will all reflect our Father in all things. This is the goal, whether male or female.

Exposition and Application

This text is not for everyone. It is not a blanket encouragement that you are forgiven no matter what. Now sure—it can be. But there are two requirements that must be met to know this text is for you. First, you must seek forgiveness through Jesus’ name. Second, you must belong to a community that gathers around his name, knowing that his name is the only place where forgiveness may be found.

Why do I say this?

Because in context, John is writing to one group of people after another group split off (1 John 2:19). John is not encouraging both groups. He is hopeful the second group will come back and find forgiveness and joy within his community again, but he knows they might refuse. And if they refuse, the encouragements he gives in our text today are not true of them.

So I beg you today—please seek Jesus. And please allow him to lead you to a Christian community where Jesus is exalted and his ethic practiced. This is how we know we know God (1 John 2:3–6).

What was Jesus’ ethic? His life revealed it. He loved people who the world—especially the religious elite—deemed unlovable. He ate with political and religious outcasts. He empowered women and brought salvation to outsiders. He brought healing even at great personal cost. He ultimately was crucified as a political and religious enemy of Rome and Judaism.

So here is the question: How does your life compare to his? Do you help and empower the marginalized—speak up for them—or do you pass by on the other side thinking, “Someone else will do something”?

This was how Jesus lived his life, and it cost him. It will cost us too. This is why Jesus told us to take up our cross and follow him (Luke 9:23).

So if you are truly following Jesus, striving to live publicly as he lived, this text is for you. And it is meant to be an encouragement.

Saint Augustine Assessment

This section of the post is for paid subscribers only. For details on this section, click here.

Gospel Plea

It is possible to know you are forgiven. It is. But it is also possible to be deceived.

I do not want you to be deceived.

Please, oh please, do not take Christ’s promise in this text in vain. Forgiveness is in his name. But his name is synonymous with love. The community he created, called the church, will be known by their love (John 13:35), not by what they stand against in the name of Jesus.

Jesus’ strongest words in Scripture were aimed at religious leaders who blocked people from God—not at sinners who needed him (Matthew 23). If you spew hatred and vitriol and have no empathy in your heart for the hurting and outcasts in our world, you do not get to claim the forgiveness of Christ.73

But if you are reading these words, there is still time to claim it. You just need to pray for Jesus to change your heart—whether you have “known” him for an hour or the past fifty years. I promise he is willing. It might not happen overnight—and it certainly will not be comfortable—but if you truly believe in him and know him, he will change you from the inside out.

As Paul told Titus, “We were once … hating one another” (Titus 3:3). That verb is huge. It adds weight to the conjunction in the next verse: “But when God our savior’s kindness and love for people appeared … he saved us” (Titus 3:4–5). Paul contrasted God’s kindness with our past apathy/active hate. The word in the text is philanthrōpia (philanthropy, “love for people”). To not grow in love that others recognize as love is to call into question the validity of your claim to know God.

But forgiveness is possible. And if you have been forgiven, change is inevitable.

Trust him for forgiveness today!

Great Commandment Plea

Let me preface this by saying: What follows does not contradict the previous section. There is an important distinction between that section and this one.

While our thinking obviously influences our actions, it is important to remember that Jesus confronted Saul about his persecution of Christians; he said nothing about Saul’s failure to believe he is God (Acts 9:4).74 As such, I believe we can have a variety of theological—even political—opinions, but we are not allowed to intentionally harm people, put up with people being harmed, or promote systems that perpetuate harm.

So here is my plea: If you are a Christian, stop telling other Christians they are not Christians just because they have different perspectives than you do. As long as they claim Christ as their hope and strive to live like he did, it does not really matter what their doctrinal positions are.

Jesus did not say they will know us by our bickering about who is in and who is out. He said they would know us by our love and unity. And if we are pursuing love and unity with each other, Jesus says we are forgiven, we know him, and have victory.

So the plea today is simple: Stop gatekeeping heaven!

Reflection Questions

- How do the reminders that you are forgiven, know God, and have conquered the evil one make you feel? Do you believe it?

- If you struggle to believe it, can you identify what is preventing your belief?

- Do you agree with the explanation presented above—that the three groups are not intended to represent stages of Christian growth? Why or why not?

- How should you treat fellow believers as a result of this text?

- What are some implications of men and women being addressed together in this text?

Thanks for reading!

In this with you!

While I am committed to providing theological reflections at no charge, your paid subscription makes my writing possible and helps me reach more people with the gospel of God’s love. If you’re not currently a paid supporter, please consider becoming a supporter today.

Buy Me a Coffee

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateWhile I am committed to providing theological reflections at no charge, your paid subscription makes my writing possible and helps me reach more people with the gospel of God’s love. If you’re not currently a paid supporter, please consider becoming a supporter today.

Buy Me a Coffee

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateNotes and References

- I read as τεκνίον because this is a Johannine term, occurring nowhere else in the NT. Also, it is more likely that a scribe would have changed to match with the word in 2:14 than for a later scribe to make the words differ. ↩︎

- I do not insert the possessive ὑμων here. The dative ὑμῖν in the text can be understood as carrying the possessive nuance (see Wallace, Greek Grammar, 149–151). ↩︎

- I ignore the variant here, because it is poorly attested, and John’s usage elsewhere prefers the masculine. ↩︎

- I read parallel with the other usages of γραφω in verse 14, despite some late witnesses reading it parallel to verses 12–13. The Vulgate is probably the earliest witness for the present tense understanding in verse 14. Reading as present would, however, create an order from oldest to youngest, but then it would be very difficult to explain the next two statements. See exegesis for further discussion. ↩︎

- I ignore the variant here, because it is poorly attested, and changes the interpretation from personal to conceptual. ↩︎

- I do not omit τοῦ θεοῦ, since Codex Vaticanus (4th century) is really the only support for the omission. ↩︎

- See Thomas, “Literary Structure,” 373. ↩︎

- See discussion in Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 66. ↩︎

- Most commentators lump 2:12–14 in with at least 2:15 – 17. The only two commentators of my ten primary conversation partners who looked at 2:12–14 as a standalone unit were Akin (1, 2, 3 John, 100–107) and Jobes (1, 2, 3 John, 100–108). ↩︎

- Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 107. ↩︎

- Jobes herself notes the connection to 5:13 in her discussion of the “declarative” understanding (1, 2, & 3 John, 106). ↩︎

- Bultmann (Johannine Epistles, 31) argues the opposite: “The ὅτι-clauses are not explicative but causal, as in vss 8 and 21. Only in this way is there an inner connection with what precedes.” I must disagree. ↩︎

- Marg Mowczko, “Where are the women in 1 John 2:12-14?” Marg Mowczko: Exploring the biblical theology of Christian egalitarianism, Published April 13, 2025, https://margmowczko.com/fathers-young-men-1-john-212-14/ (Accessed January 26, 2026). ↩︎

- Is the cleansing of 1 John 1:9 purposefully absent here? The only times forgiveness is mentioned in 1 John is 1:9 and 2:12; the only times “cleansing” is mentioned is 1 John 1:7, 9. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 2.4, p. 42. ↩︎

- Whether or not this is intentional will await discussion at the end of the section. ↩︎

- See Brown, The Epistles of John, 303; Bultmann, Johannine Epistles, 32. ↩︎

- He is referred to as a νεανίσκος in 19:20, 22. ↩︎

- See Philo, On the Creation of the World 103–105, cited in Lieu, I, II, & III John, 87. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 304. ↩︎

- Lieu, I, II, & III John, 89. ↩︎

- Two commentators who understand 2-3 John as preceding 1 John are Strecker, The Johannine Letters, 3; and Marshall, The Epistles of John, v. ↩︎

- Lieu, I, II, & III John, 86. ↩︎

- Rudolf Schnackenburg, Die Johannesbriefe, HTKZNT (Freiburg: Herder, 1984), 125–126. It should be noted that his reference of 1 Corinthians 5:11 is highly debatable, though it does make for an interesting reading of that text. ↩︎

- Bultmann, Johannine Epistles, 31. ↩︎

- See Philo, On the Creation of the World 103–105, cited in Lieu, I, II, & III John, 87. ↩︎

- It should be noted that some manuscripts alter τεκνία in 2:12 to παιδία so it matches 2:14 here. There is a long history of viewing these as the same group. ↩︎

- Mowczko, “Where are the women?” (see note 13 above for the link). ↩︎

- Westcott, Epistles, 61. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 298. ↩︎

- Bultmann, Johannine Epistles, 32. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 305. ↩︎

- Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 105. ↩︎

- Bultmann, Johannine Epistles, 32. ↩︎

- Bultmann, Johannine Epistles, 32. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 306. ↩︎

- Bultmann, Johannine Epistles, 25. ↩︎

- See discussion in Akin, 1, 2, 3 John, 107; Yarbrough, 1–3 John, 123–125. ↩︎

- For a thorough discussion of a Christocentric hermeneutic, see Gregory A Boyd, The Crucifixion of the Warrior God: Interpreting the Old Testament’s Violent Portraits of God in Light of the Cross, 2 volumes (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2017); see also Graeme Goldsworthy, Gospel-Centered Hermeneutics: Foundations and Principles of Evangelical Biblical Interpretation (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2006); Sidney Greidanus, Preaching Christ from the Old Testament: A Contemporary Hermeneutical Method (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1999). ↩︎

- See Lieu, I, II, & III John, 89. ↩︎

- See Brown, The Epistles of John, 298. ↩︎

- Bultmann, Johannine Epistles, 31; Brown, The Epistles of John, 298–300; Strecker, The Johannine Letters, 56; Yarbrough, 1–3 John, 114; Brown also highlights Schnackenburg, Spicq, and Westcott among those holding this position (Epistles of John, 298). ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 298. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 299. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 299: “It is well known that in some works of the NT presbyteros serves as a designation for senior church officers, for all practical purposes equivalent with episkopos. It is less well known that neōteros (neaniskos) serves as a designation for junior church officers, equivalent to diakonos.” ↩︎

- T. Longman III, “Merism,” in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings, ed. Peter Enns (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2008), 464. ↩︎

- Calvin (Commentaries on the Catholic Epistles, 183): “He comes now to enumerate different ages, that he might shew that what he taught was suitable to every one of them. For a general address sometimes produces less effect; yea, such is our perversity, that few think that what is addressed to all belongs to them. The old for the most part excuse themselves, because they have exceeded the age of learning; children refuse to learn, as they are not yet old enough; men of middle age do not attend, because they are occupied with other pursuits. Lest, then, any should exempt themselves, he accommodates the Gospel to all.” ↩︎

- Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 69. Emphasis in original. ↩︎

- However, it is possible, as our next text will show, John wants to emphasize that spiritual “children” are more likely to stumble and fall for the lies of the evil one than more mature believers, though Lieu notes 4:4 as a counter to this idea (I, II, & III John, 89). ↩︎

- Lieu, I, II, & III John, 87. ↩︎

- Again, it is worth noting that Carson (“John, Letters of,” 403) sees Jeremiah 31:34 behind 1 John 2:27. This is another text that supports that understanding. Other commentators who recognize 1 John 2:12–14 as influenced by the New Covenant are Brown (The Epistles of John, 320); Smalley (1, 2, 3 John, 72; Akin (1, 2, 3 John, 106); Jobes (1, 2, 3 John, 107). ↩︎

- This would also explain the ordering of the age groups. “Fathers” has to follow “children” to highlight the connection between being a father and knowing the Father. ↩︎

- Perhaps this is partly what Athanasius means in On the Incarnation 54 when he says, “He was incarnate that we might be made god” (as found in the translation by John Behr in the Popular Patristics series [Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011], 107). Regardless, the Eastern doctrine of theosis is a deep well that we western Christians would do well to explore. It definitely has some biblical, and especially Johannine, roots. ↩︎

- Some moderns might refer to “Mother God,” but nowhere do we see “Parent God.” ↩︎

- Lieu, I, II, & III John, 87. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 300. ↩︎

- On ἀδελφὸς, see BDAG 18; BDAG 81 highlights that ἄνθρωπος is best translated “human being” even in the singular. ↩︎

- Mowczko, “Where are the women?” (see note 13 above for the link). ↩︎

- BDAG 786. ↩︎

- Mowczko, “Where are the women?” [see note 13 above for the link]). This is another reason to not view the text as stages. Doing so would imply that women can only ever be “new believers”—an inherently and incredibly sexist position. ↩︎

- Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 106. Mowczko helpfully points out the poetic nature of the text indicates we should refrain from taking the identifiers too literally (Mowczko, “Where are the women?” [see note 13 above for the link]). ↩︎

- Strecker, The Johannine Letters, 56. ↩︎

- Brown, The Community, 183–198: “The importance of women in the Johannine community is seen not only by comparing them with male figures from the Synoptic tradition but also by studying their place within peculiarly Johannine patterns” (191). He specifically notes the Samaritan woman; Mary Magdalene; Mary and Martha; and Mary, the mother of Jesus. ↩︎

- See Stott, The Letters of John, 100, for this language. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 298. ↩︎

- Stott, The Letters of John, 100. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 2.6, p. 44. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 2.7, p. 44. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 2.8, p. 44. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 2.2, p. 40: “Don’t let those that have been cut off lead you astray, so that you are cut off. Instead, urge those that have been cut off to re-insert themselves once more.” This citation supports the argument that at this point in Augustine’s dealings with the Donatists, he had not yet embraced the political compulsion route: “Urge those … to re-insert themselves.” ↩︎

- However, Matthew Barrett would flip the script and say that if this line of thinking is at all accurate, the opposite is actually the case, and Protestants are now the “true church” (see Reformation as Renewal, 879). ↩︎

- E.g., Christ is God, salvation in Jesus alone. In other words, the content of the Apostles and Nicene Creeds. ↩︎

- It is possible universalism is true and all are saved in the end, but on the potential that this is wishful thinking, you need forgiveness to escape hellfire. Please do not ignore this message. ↩︎

- Though it should also be noted that Saul, who later became Paul, went on to write incredible texts that highlight Christ’s divinity: 1 Corinthians 8:6; Philippians 2:5–11; Colossians 1:15–20; Romans 9:5; Titus 2:13–14 ↩︎