The first post in this series can be found here.

The title of this post is purposefully borrowed from Mark Dever’s book, Nine Marks of a Healthy Church.1 It does not take a lot of searching that book and comparing it with this text in 1 John to see that his book is not as biblical as many might think (despite a plethora of Scripture references throughout).2 You see, according to John, the Church exists where Christians allow the light of God to illuminate their lives, showing it for what it is; where Christians confess their sins to one another rather than hiding them and feigning holiness or perfection; where Christians walk with one another in patience and grace, modeling the grace and truth and love of Jesus to one another—day-in and day-out.3

You see, the Church has gotten it backwards for too long. We have taken what was meant for insiders (confession, recognition of sinfulness) and preached it to the world instead of to ourselves. We have blocked the way to salvation to others and earned the title “hypocrites” in the process. John’s first main point in his letter is to lay out Community expectations, not universal expectations.

Let’s look at it together!

1 John 1:5–2:2

15And this is the message4 which we have heard from him and are announcing to you: “God is light, and there is absolutely no darkness in him.” 6If we say that we presently have fellowship with him, but we are walking in the darkness, we are lying and we are not doing the truth. 7If we are walking in the light5 as he himself is in the light, then we presently have fellowship with one another, and the blood of Jesus6 his son is purifying7 us from all sin. 8If we say that we have no sin, we are deceiving ourselves and the truth8 is not in us. 9If we confess our sins, he is faithful and righteous to forgive our9 sins and to purify10 us from all unrighteousness. 10If we say that we have not sinned,11 we make him a liar, and his word is not in us. 21My little children, I am writing these things to you in order that you might not sin.12 But if anyone might sin, we have an advocate with the Father: Jesus Christ the righteous one. 2He is the expiation for our sins, but not only13 for ours, but also for the whole world.

The footnotes above discuss textual variants. The bold numbers are verse numbers.

Jump menu

Exposition and Application

Saint Augustine Assessment

Gospel Plea

Great Commandment Plea

Reflection Questions

Exegetical details

This portion of scripture is a lot more straight forward than the previous. Here John builds on themes that he previously discussed in 1:1–4, and he introduces other concepts that he will build on throughout 1 John. Some of the primary themes that get further focus here are Jesus (Christ) in 1:7 and 2:1, after being initially introduced in 1:3; God as “Father” in 2:1, after being initially introduced in 1:2–3; the idea of “fellowship” in 1:6–7, after being initially introduced in 1:3; the idea of logos in 1:10, after being initially introduced in 1:1; and the repetition of the first-person plural pronoun in 1:7–10 and 2:2, after being introduced in each of 1:1–4.

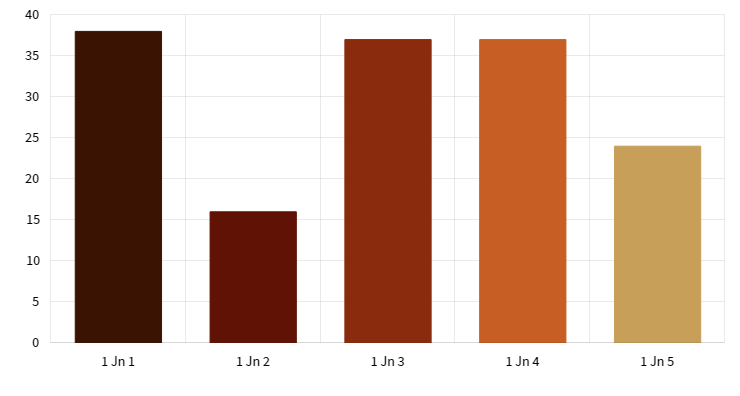

The proliferation of first-person plural pronouns can be understood as carrying on the idea of κοινωνία—John’s purpose according to 1:3—even though that word ceases to occur after 1:7. As Table 1 illustrates, there are 155 uses of we/us/our in the five chapters of 1 John.14 By way of comparison, James—another book with 5 chapters—only has 21 uses of we/us/our; 1 Peter has 5 uses of we/us/our in its 5 chapters, located within three verses (1:3 [2x]; 2:24 [2x]; 4:17); in the whole New Testament (see Table 2), the only books with more usages of we/us/our than 1 John are Acts (238 uses in 28 chapters) and 2 Corinthians (215 uses in 13 chapters). However, another five chapter book, 1 Thessalonians, comes close with 97 uses of we/us/our.

1:5. And this is the message (Καὶ ἔστιν αὕτη ἡ ἀγγελία). The “message” here is directly related to the “announcement” described last time. In 1:3, John said, “What we have seen and have heard we are announcing also to you in order that you also might continuously have fellowship with us.” In order for the fellowship discussed above as so central to this book (and stated by John as his whole purpose for writing) to be achieved, it must be centered around an objective message. This is the message that John describes in this verse and draws implications from throughout the rest of this section.

Which we have heard from him and are announcing to you (ἣν ἀκηκόαμεν ἀπʼ αὐτοῦ καὶ ἀναγγέλλομεν ὑμῖν). This language recalls again, the idea of 1:1–4. While the word ἀναγγέλλομεν (here) is slightly different from ἀπαγγέλλομεν (1:2, 3), they are both still from the same root as ἀγγελία in the prior clause. Raymond Brown notes that John’s primary usage of ἀναγγέλλω is in the context of the Holy Spirit’s teaching in John 16.15 This lends some credence to Carson’s perspective that one Old Testament text behind 1 John is Jeremiah 31:31–34.16 A comparison of these texts reveals the parallel ideas:

- “I will surely give my laws into their minds and upon their hearts I will write them, and I will be their God, and they will be my people, and they will never teach each one his fellow-citizen and each one his brother, saying, ‘Know the Lord,’ because they will all know me, from the smallest even to the greatest, because I will be merciful to their unrighteousness and their sins I will never remember again.” — Jeremiah 38:33b–34 (LXX)17

- “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all truth, for he will not speak from himself, but what he hears he will speak, and will announce the coming things to you. He will glorify me, because he will take from me and announce to you. Everything the Father has is mine. This is why I said, ‘He will take from me and announce to you.’” — John 16:13–15

Though some would insist on verbal parallels to justify identifying a source,18 the conceptual resonance is unmistakable: a new source of knowledge. Both passages are referring to the implications of the implementation of the New Covenant. Carson explains that no Christian has a higher claim to the truth than any other, “for all of God’s true people share the same anointing.”19

- “And this is the message which we have heard from him and are announcing to you.” — 1 John 1:5a

- “When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all truth, for he will not speak from himself, but what he hears he will speak, and will announce the coming things to you.” — John 16:13

Brown explains that “almost everything said about the Paraclete in [John’s Gospel] had earlier been said about Jesus, so that the Paraclete is to Jesus as Jesus is to the Father. The epistolary author has the same mentality, but he emphasizes the ‘we’ instead of the Paraclete.”20 The rest of 1 John—a special focus of 1:5–2:2—seeks to differentiate the voice of the Holy Spirit from false spirits. False spirits will steal from fellowship, will shipwreck joy, and will cost their hearers their assurance (cf. 1:3, 4; 5:13).

“God is light, and there is absolutely no darkness in him” (ὅτι ὁ θεὸς φῶς ἐστιν καὶ σκοτία ἐν αὐτῷ οὐκ ἔστιν οὐδεμία). The ὅτι introduces this as the substance of the message. This is the Holy Spirit’s message. A direct teaching from God. A message that will be expanded and explained throughout the rest of 1 John. John presents this statement as God’s message to Jesus, that Jesus shared with the Spirit, and that the Spirit now proclaims through the Church. When we read it in context with 1:3–4, it becomes crystal clear that this is a reality on which our joy, fellowship, and assurance depend;21 Brown even translates ἀγγελία as “gospel” to highlight the central nature of this claim.22 John goes on in 1:6–2:2 to present three sets of antitheses to determine if his readers are walking in the light or darkness, and—by extension—if they are experiencing joy, fellowship, and assurance.

However, before moving into the three sets of antitheses, several other points must be discussed related to the idea that God is light. There is an allusion here to Genesis 1 and the Creation story; we have to consider the idea of light as the ancients would have understood it; and whether or not the claim “God is light” has metaphysical implications.

First, Genesis 1:1–4 (LXX) reads,

In the beginning, God made the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was invisible and unformed, and darkness was upon the abyss, and the Spirit of God was turning upon the waters. And God said, “Let there be light.” And there was light. And God saw that the light was good. And God separated the light from the darkness.

If we think back to 1 John 1:1, he said that the message he is announcing was “from the beginning.” The very first act of God in creation was light. Light has been around since the beginning.23 And when God created light, he called it good and separated it from darkness. Light is good. God created light. Where God is there is light. And John is clear that “there is absolutely no darkness in him” (1:5).24 But how did the ancients understand light?

Lieu is incredibly helpful at this point, noting that “for obvious reasons, particularly in a world without multiple possibilities of artificial light … light represents life, hope, blessing, and also that which is not ashamed to be seen.”25 The ancients could not flip a switch and fill a room with light. They were dependent on the sun, and if they needed light after the sun went down, they required torches or candles. Light for them represented safety, protection, and peace, whereas darkness represented danger, vulnerability, and fear. When John writes that “God is light,” he is establishing that eternal life26 is found where God is.

But is God’s very essence light? It might be tempting to take this approach, but as Bultmann notes, “This sentence no more defines the nature of God as he is in himself than does ὁ θεὸς ἀγάπη ἐστίν (‘God is love,’ 4:8, 16) and πνεῦμα ὁ θεός (‘God is Spirit,’ Jn 4:24).”27 Anselm might disagree.28 But “John is not drawing on philosophical ideas of the pure intellectual realm, nor is he concerned to emphasize the otherness of God or the means by which God can be apprehended, but rather the consequences in living of making such a claim.”29 John presents “God is light” as a metaphor to help us understand the workings of God, and—by implication—how his children should conduct themselves as well.30 However, what might surprise us is that morals themselves are not explicitly preached in 1:6–2:2, though John certainly does present moral implications.

1:6–2:2. Before moving into the exegesis proper for these verses, it is worth noting some commonalities amongst these verses. Verses 6, 8, and 10 present claims made by some that John shows to be erroneous. They are presented as if anyone—including John himself—might be capable of making these claims (“If we say”). Verses 7, 9, and 2:1 present the contrast to the prior claims. It is especially interesting to note that the claims are just that—claims—whereas the antitheses are actions that result in the application of the gospel (cf. 1 John 3:18).

As will be made clear throughout the exegesis, this text (and by implication the whole book) does not fit easily in our theological systems that teach:

(Regeneration –> ) Faith –> Justification –> Sanctification –> Glorification

Rather, John’s understanding looks like:

Openness to God –> Closeness to God –> Fellowship with God’s Children –>

Conviction of Sin –> Cleansing from Sin –> Victory over Sin

No one living has arrived yet, and no one is guaranteed to stay victorious. Ongoing victory depends on maintaining fellowship with God and others, but if someone throws in the towel at some point, their lack of horizontal fellowship reveals their lack of joy and assurance. It is what this letter was written to combat (1:3, 4; 5:13).

6. If we say that we presently have fellowship with him (ἐὰν εἴπωμεν ὅτι κοινωνίαν ἔχομεν μετʼ αὐτοῦ). This and the other antitheses are constructed as third-class conditionals: “ἐάν followed by a subjunctive mood in any tense.”31 While there is some debate about exactly what a third-class conditional indicates, Akin helpfully cuts through the noise by labelling them as cause-effect in this text.32

The claim here is present fellowship with God.33 But the next clause clarifies that behavior must match the claim.

But we are walking in the darkness (καὶ ἐν τῷ σκότει περιπατῶμεν). This phrase indicates a behavior inconsistent with holding fellowship with God. John does not detail what this looks like practically here, though given everything we do have in 1:6–2:2—and the rest of the book—it seems clear that Christian fellowship is involved (see especially on 1:7 below). The ultimate sign of walking in the dark is forsaking the brothers (1 John 2:19), though claiming to love while failing to live in love (3:18) would also qualify as walking in the darkness.

The term for “walking” is important. It is a Hebraism that denotes a lifestyle.34 Smalley highlights that the present tense (which occurs 18 times throughout 1:6–2:2) “denotes continuity.”35 John does not write, “If we walked in the darkness,” because this would cut off all hope of salvation for everyone; the present tense throughout this section holds out hope for deficient Christianity to be abandoned in favor of the reality.36

We are lying and we are not doing the truth (ψευδόμεθα καὶ οὐ ποιοῦμεν τὴν ἀλήθειαν). The reality of the lie is obvious. In 1:5, John explained that God is light, and in the previous clause John said that there are some who claim to be in fellowship with God but walk in the darkness. Bultmann helpfully notes that lying “is not simply accidental, but is rather a characteristic of ‘walking in the darkness.’”37

It is at this point that we must heed Yarbrough’s caution: “Optimal interpretation of a letter involves determining, if possible, the purpose(s) for which the author wrote it.”38 As we have noted throughout, John’s purpose is not to offer tests to discern true believers from false ones. He is writing to promote Christian fellowship.39 To start defining what it means to walk in the light/darkness by importing texts external to 1 John is to potentially derail John’s whole argument. But this will be clarified as we continue.

7. If we are walking in the light as he himself is in the light (ἐὰν ἐν τῷ φωτὶ περιπατῶμεν, ὡς αὐτός ἐστιν ἐν τῷ φωτί). The verses of this antithesis (1:6–7) are tightly connected to one another. In fact, a chiasm is present:

This phrase again reiterates that God is light, though this time by highlighting God’s existence “in the light.”40 One wonders if this is referring to Christ, emphasizing his earthly life more than his exalted state, since it varies from the formula in 1:5. However, this need not downplay our faith in Christ’s divinity. Behr explains, “The divinity of Jesus is expressed in the New Testament primarily by ascribing to him all the activities and properties that, in Scripture, belong to God alone, such as creating (Jn 1:3), bestowing life (Jn 6:35; Acts 3:15), forgiving sins (Mk 2:5–7), raising the dead (Lk 7:14–15), and being the recipient of prayers (Acts 7:59).”41 Another property ascribed to God in the Old Testament is found in Psalm 104:2; Daniel 2:22, and Isaiah 2:5, and according to Brown, this “new image has better biblical parallels” than the simple: “God is light” of 1:5.42 So whether it is speaking of God or of Christ, the point is the same.43

While John does not explain what “walking in the light” looks like practically in this text, he does connect it to Jesus’ own life, and the rest of the book will expand on this idea. However, he does make it clear that walking in the light is incompatible with walking alone.

Then we presently have fellowship with one another (κοινωνίαν ἔχομεν μετʼ ἀλλήλων). This is the goal toward which John has been building since 1:3a, “in order that you also might continuously have fellowship with us.” Bultmann betrays his inability to interpret the text as it stands when he notes the difference between the “fellowship” of 1:6 and the “fellowship” here, writing, “In all likelihood, [fellowship with God] is what stood in the conjectured Source, but the author of the Epistle probably changed it to “with one another” with the thought that the reader needs to know in what walking in the light, as opposed to walking ‘in the darkness’ (v 6), consists.”44 But we do not need to posit an earlier version of this message. John told us what he means here in 1:3b—“Our fellowship, indeed, is with the Father and with his Son, Jesus Christ.” Christian fellowship involves fellowship with God and Christ. It is easy to claim the vertical, invisible fellowship, but John makes it clear that this is impossible apart from the visible, horizontal fellowship. Strecker explains, “The author is determined to say that union with God is the foundation of Christian ‘walking in light,’ and that the community among Christians exists on that basis.”45

Augustine asks, “And what do we do with our sins?”46 And it is a valid question, because to this point Christian fellowship has been established and exhorted with no reference to sin or to the cross.

And the blood of Jesus his son is purifying us from all sin (καὶ τὸ αἷμα Ἰησοῦ τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ καθαρίζει ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ πάσης ἁμαρτίας). This phrase indicates the results of being in horizontal fellowship with others. Bultmann again struggles with the text:

The idea that “having fellowship with one another” is the condition for purification stands in contradiction to v 9, where the condition is confession of sin. It all amounts to this: the sentence, the blood of Jesus cleanses us from sin, corresponds, indeed, to the ecclesiastical theology, but not to Johannine thought.47

Alternatively, as we have already noted, God is present in the community, so there is a clear connection between the presence of God and Christ and the presence of the Church.48 This is why confession to “one another” can be seen both as part of “fellowship with one another” and as confession to God.49 As Jobes puts it:

The more unexpected statement that mentions fellowship with “one another” (ἀλλήλων) introduces the thought that fellowship with God and fellowship in the Christian community are intimately related. Only when believers are walking in the light can we have fellowship with God, a fellowship that is embodied as fellowship with one another.50

There is no contradiction here. This is the beauty of Christian fellowship, and why fellowship with one another is walking in the light: it exposes our sin and results in our cleansing from it.51

But note what John does. And he clearly does it in each of these antitheses. He paints the right path in gospel terms: Jesus, blood, purification, forgiveness. And the purification John speaks of here is in the present tense. It is not completed. It is in process. It is why John adds the next two antitheses. Whereas the wrong path is painted in increasingly dismal strokes, the hope of the gospel grows wider. Verse 10 might accuse some of making God a liar, but 2:2 says that Jesus’ work extends to the whole world.

8. If we say that we have no sin (ἐὰν εἴπωμεν ὅτι ἁμαρτίαν οὐκ ἔχομεν). This antithesis builds directly off the previous. True fellowship results in cleansing from sin, but those who had fled the fellowship have a response: “We do not need cleansing from sin, because we do not sin.”

The translation here could be altered slightly to demonstrate that the grammar and construction is identical to “presently have fellowship” (κοινωνίαν ἔχομεν) in 1:7. This could be translated as “If we say that we presently have no sin” to match 1:7, but since most commentators agree that the idea here is an ongoing claim of sinlessness,52 I have left my translation as is.

We are deceiving ourselves (ἑαυτοὺς πλανῶμεν). This statement demonstrates the danger of claiming to be without sin. Jobes writes:

How many ways are there to deny sin? One might claim perfection in Christ. One might reason that anything a Christian does must be okay. Or one might simply define what one does as not sin—a phenomenon increasingly seen in societies where what is legal is not necessarily morally righteous as God defines it.53

Regardless, this verse is not saying, “Look at them and how sinful they are.” Rather, it is asking those who call themselves Christians to consider how sinful we are. If we brush aside our own sin, then the nonbelievers outside our walls might be closer to God than we are. Perhaps our mistaken portrayal of sin is why they feel like they cannot know God—they know they are not perfect. John sets the record straight here. Have we deceived ourselves by acting like sin is only a them problem?

And the truth is not in us (καὶ ἡ ἀλήθεια οὐκ ἔστιν ἐν ἡμῖν). This phrase is the inevitable consequence of deceiving ourselves. Strecker writes, “No one who has been received into the truth can deny that she or he is a sinner.”54 And Augustine explains the reverse, “If you confess that you are a sinner, then, the truth is in you, for the truth itself is light,”55 preparing the way for the alternative to claiming sinlessness.

9. If we confess our sins (ἐὰν ὁμολογῶμεν τὰς ἁμαρτίας ἡμῶν). Just like “we have no sin” was a present claim in 1:8, so the act of confessing here is a present reality. “Confess” comes from ὁμολογέω, made up of two words—ὁμός: “same,” and λέγω: “I say”—literally meaning, “I say the same as.” Those who claim sinlessness are lying and deceived (and in 1:10 making God a liar) because they do not say what God says.56

The Christian life is a life of continued confession. It is not a one-and-done event. The very idea of fellowship requires this. It is why it would be so much easier to remove oneself from the local church. It is why searching for the “perfect church” will always fail. It is why Jesus said what he did in Matthew 18:15–17. Interpersonal relationships are ripe for sin; living in communion with others will regularly require us to confess our sins. “John’s point is that the true condition for fellowship is the confession of our sins.”57

There is some debate about the reference to “sins” (plural) here. Smalley posits that it “probably indicates that the confession of particular acts of sin is meant in this context, rather than the acknowledgment of ‘sin’ in general.”58 However, Strecker writes:

The concept of ἁμαρτία, which here appears in the plural, does not offer much support for such a conclusion, for while the plural refers to individual sins it is clear that in the context the singular πᾶσα ἁμαρτία (v. 7; also πᾶσα ἀδικία, v. 9) has the same generalizing import and applies to individual sins (cf. 5:17). The shift between singular and plural is not to be understood as a material difference.59

Strecker is correct, though I find Smalley’s stance helpful. Jobes adds, “Wisdom suggests that the confession of sin should be confined to those with knowledge of the sin.”60

He is faithful and righteous to forgive our sins (πιστός ἐστιν καὶ δίκαιος ἵνα ἀφῇ ἡμῖν τὰς ἁμαρτίας). The result of our confessing sin is that God will forgive us. In order to grasp the importance of this verse, it is worth considering the meaning of the term “sin,” the OT precedent for “forgiveness,” and the fact that John ties all of this to the character of God (Christ). While more could be said on these topics, hopefully what is said will spur further reflection and research.

John himself defines sin later in this work. In 3:4, he writes, “Sin is lawlessness.”61 While the word “law” (νόμος) never occurs in 1 John, the word “commandment” (ἐντολή) does a lot. Louw and Nida explain,

The difference between ‘a law’ and ‘a command’ is that a law is enforced by sanctions from a society, while a command carries only the sanctions of the individual who commands. When, however, the people of Israel accepted the commands of God as the rules which they would follow and enforce, these became their laws.62

For those who have entered into the Christian community, the commands (ἐντολή) that John describes throughout have assumed the status of laws. Rather than scouring the Bible to see which commands John expects us to follow (a list that will vary for every commentator), John’s list is simple: “This is his command: in order that we might believe in the name of his son, Jesus Christ, and love one another, just as he gave a command to us” (3:23). There are twelve more occurrences of “command” (ἐντολή) throughout 1 John, including six of them in our next text, so we will get more specific when we can. But for now, it is worth reiterating that we need to understand “sin” as John taught sin: failing to believe in Jesus and breaking Jesus’ commandment to love. These are the sins that we must confess; when we do we will receive forgiveness.

But what is “forgiveness”? In order to do this conversation justice, it is worth tying in two Old Testament passages: Psalm 130 [LXX 129]63 and Exodus 34:6–7.64 In English translations of both of these passages, we find the word “forgive,” though it is used as a verb in Exodus and as a noun in the psalm. The Hebrew words behind both are seemingly unrelated (נשׂא in Exodus; סְלִיחָה in the psalm), but in Nehemiah 9:17, the author paraphrases Exodus 34:7 with סְלִיחָה instead of נשׂא. In Psalm 129:3–4 LXX, the author writes, “If you counted lawlessness, Lord, Lord, who could endure? Because hilasmos is with you.” I left the word untranslated, because while the Hebrew Bible reads “forgiveness” (סְלִיחָה), the LXX uses a word that is critical to our section of 1 John. And it is a word that is heavily debated.65 The true meaning of forgiveness will be realized when we reach 1 John 2:2. But “forgiveness” is an essential action that God performs. It is part of his character.

And that is probably what it means by “he is faithful and righteous.” He is true to himself; he is true to his promises. Look at Exodus 34:6–7 (the italicized words represent ideas corresponding to 1 John):

The Lord, the compassionate and merciful God, slow to anger and full of mercy and truth, and keeping righteousness and showing mercy to thousands, forgiving lawlessness and unrighteousness and sin, but he will not cleanse the guilty, bringing the lawlessness of fathers upon children, and upon children’s children until the third and fourth generation.

As Lieu explains, “It is intrinsic to God’s self-revelation to Moses in Exod 34:6–7 that

forgiveness is rooted in the very character of God.”66 While she explicitly states that this text does not explain the phrase “faithful and righteous,”67 “truth” implies trustworthiness (faithful), “keeping righteousness” relates to his status as righteous, and his act of “forgiving” relates to John’s claim that he will forgive those who confess their sins. But that is not all.

And to purify us from all unrighteousness (καὶ καθαρίσῃ ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ πάσης ἀδικίας). This phrase carries the results of our confession even farther. And it again builds off Exodus 34. Whereas the Hebrew Bible says that God “will not clear [נקה] the guilty,” the LXX reads “will not cleanse [καθαρίζω] the guilty.” 68But this is still further proof that John is pulling from Exodus 34. God will not cleanse the guilty,69 but those who confess their guilt will be forgiven and cleansed. But why does God forgive and cleanse those who confess their sins but not forgive or cleanse those who do not confess their sins?

10. If we say that we have not sinned (ἐὰν εἴπωμεν ὅτι οὐχ ἡμαρτήκαμεν). This one is very similar to 1:8. The difference is that in 1:8, “sin” was the object of the verb “have.” Here, “sin” is the verb itself. But it is worth noting that while “We do not have sin” (1:8) was a present-tense claim, this claim is about a past action (the form ἡμαρτήκαμεν is perfect). As Wallace explains, “The emphasis is on the completed event in the past time rather than the present results.”70 It is likely John is referring to the claim that schism from the Church (the one described in 2:19 as past) was not sin. But John notes that not only was it sin, but it keeps the perpetrators in sin because they continue to refuse fellowship (and confession) with the Church. Yarbrough writes:

In a Western individualist climate, it is wise to keep squarely in view the social connotation of words from John’s more communitarian social setting. For early church leaders like John, the authenticity of reception of God’s Word had both personal and social criteria. This helps to account for John’s concern, expressed later in the epistle, about those who fail to care for others.

We make him a liar (ψεύστην ποιοῦμεν αὐτόν). This reality is the other side of the coin of the reality expressed in 1:6. There, a claim to walk in light while really walking in the dark meant the boasters were “not doing (ποιοῦμεν) the truth.” Here, John makes it plain that one way people walk in the dark is by claiming certain sins are not sins. When they do this, they “make (ποιοῦμεν) [God] a liar.” In other words: Doing the truth showcases that God is true and trustworthy; failing to do the truth causes others to doubt the reality that God is truly faithful and righteous to forgive our sins (like it says in 1:9), which has the lamentable consequence of keeping them from the eternal life (quality, not quantity) that God desires for them.71 This portion of Scripture has apologetics written all over it.72

And his word is not in us (καὶ ὁ λόγος αὐτοῦ οὐκ ἔστιν ἐν ἡμῖν). This phrase is the logical consequence of making God a liar. To claim a sin is not a sin is to claim that you do not need to confess. Refusal to confess is to insist that God is a liar, because he commanded that we love one another and show unity (1 John 3:23; cf. John 13:34–35; 17:20–23). When we fail to do this—worse, when we insist that it is not necessary or not sinful to refuse to do this—we prove that his message (λόγος) is not in us.73 We might give lip service to believing in Jesus, to keeping his commandments, but when we refuse to confess, we prove that his message has not yet transformed our hearts, even if it bounces around in our heads. As Strecker helpfully points out:

The Christian community itself is continually under siege, and not only because it is threatened by false prophets. It is always facing the question of assenting to God, of acknowledging God as the judging and pardoning, condemning and forgiving God and Father of Jesus Christ, and allowing God’s word to be done in it, or else of closing itself to that offer. In regard to its attitude to God and fellow human beings, the community is asked whether it will acknowledge its sinfulness, confess its sins, and allow itself to be lifted up and healed through the atoning action of God in the death of Jesus Christ on the cross.74

How often have we heard God speaking but shut our ears to it, saying, “That is not sin!” or “They are the ones who are really in sin!”? Lack of fellowship, lack of community, lack of love, lack of outreach. These are the sins John writes against throughout his book. They are sins we must again elevate to the “deadly” level (1 John 5:16; Proverbs 6:16–19).75

2:1. My little children, I am writing these things to you in order that you might not sin (Τεκνία μου ταῦτα γράφω ὑμῖν ἵνα μὴ ἁμάρτητε). This a parenthetical statement76 to clarify what he is not saying. John has made it clear that Christians sin. He has made it clear that sin is darkness and a dangerous place to live. He has offered confession and fellowship as the alternative to sin. But here he offers another purpose for his letter. He writes in order that his readers not sin.

Bultmann thinks this purpose statement solely refers to 1:8–10,77 but a better interpretation—consistent with where we have already been going—would argue that it refers to the whole letter. John includes it here to make sure that no one gets the wrong idea from what he has written thus far. Just because we all sin does not mean we should be okay with our sin. Luther cites Augustine, saying, “To have sin is one thing; to sin is something else.”78

Luther introduces his discussion of 2:1 by writing, “He who can make this text intelligible to us should be called a theologian.”79 Yarbrough has gone so far in his attempt to make sense of this text that he has created a graph with eight “octants” in which a person might find himself or herself, only one of them being right for a Christian.80 However, it is worth noting that this overcomplicates the situation. The Greek root for “sin” (αμαρτανω) occurs eight times between 1:7–2:2. In three of these cases they are verbs (1:10; 2:1 [2x]). I believe what John is doing here in 2:1 is saying, “I am writing this whole letter in an effort to keep you from going the way they went.”

But if anyone might sin (καὶ ἐάν τις ἁμάρτῃ). The parenthetical comment complete, John now offers the alternative protasis of the third antithesis. Whereas both of the previous alternative protases were constructed ἐάν + first-person plural verb, this one receives the indefinite ponoun “anyone” (τις). Brown explains this choice as “perhaps stylistic, perhaps because the contents of this condition are more negative than in the previous examples and so he prefers a hypothetic subject.”81 A better explanation is that—again—John is explaining that for those who have gone out (2:19), they need not remain there.82

We have an advocate with the Father (παράκλητον ἔχομεν πρὸς τὸν πατέρα). Here, John reverts back to “we.” But this need not nullify my working thesis about τις in the prior clause. If anyone sins—whether presently part of the Church, never part of the Church, or formerly part of the Church—the advocate with the Father is ours: the Church’s. In order to experience Christ’s advocacy for our sin, John says, you must belong to the fellowship of the Church.83 The word for “advocate” here is the same word Jesus uses to describe the Holy Spirit in John 14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7. But here, it is not referring to the Holy Spirit.

Jesus Christ the righteous one (Ἰησοῦν Χριστὸν δίκαιον). This phrase is in apposition to the accusative παράκλητον (“advocate”) from above. It is this verse that draws out the reality that the one who is “faithful and righteous” (1:9) is Jesus himself.84 It is easy to assume it, but Jesus is never named in that verse.

Luther comments on Christ’s righteousness:

He is righteous and unstained. He is without sin. Whatever righteousness I have, this my Comforter has, He who cries out for me to the Father: “Spare him, and he has been spared! Forgive him! Help him!” The righteousness of Jesus Christ is standing on our side. For the righteousness of God in Him is ours.85

That will preach. But unfortunately, it misses the context. And notes like Smalley’s do the same:

On the basis of his own righteousness, manifested above all in the righteous act of the cross (cf. v 2), Jesus is supremely able to ask for that righteousness to be extended to all God’s children who are in fellowship with him. On that ground, also, God (who is himself “righteous,” v 9a) can “purify us every kind of unrighteousness” (v 9b; cf. Rom 3:26).86

While the word “righteous” has been infused with courtroom, legal-standing, “guilt-vs-innocence” connotations in our post-Reformation, Protestant Christendom, this cannot be what John intended. A glance through the book at the root δικη reveals 11 occurrences. All of the references to “righteousness” (δικη) in 1 John refer to visible righteousness, not imputed righteousness, and God’s righteousness is often listed as the example ours is supposed to imitate.87

So when John says that “we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous one,” Jesus’ righteousness should affect our understanding of Jesus as our advocate. Smalley notes, “In classical literature and also in Philo the term παράκλητος is thus used to mean ‘one who is called alongside (to help).’”88 So if this exegesis is on the right track at this point, John explains that our advocate is righteous—he models obedience to his command (John 13:34; 1 John 3:10, 16; 4:9–10)—and can guide us back to the Church.89 But his advocacy is also more than that, and John lays it out in 2:2.90

2. He is the expiation for our sins (καὶ αὐτὸς ἱλασμός ἐστιν περὶ τῶν ἁμαρτιῶν ἡμῶν). This phrase clarifies the work of Christ for us. Specifically, it clarifies what his advocacy does. And this verse is a minefield of debate. However, given everything that has been said to this point, I am going to focus on understanding this text in context and save a post about the systematic theology implications of this exegesis for another time.

The debated word here is ἱλασμός (expiation), and even that translation is debated. Brown notes the following possible English translations: “atonement, atoning sacrifice, expiation, propitiation, remedy for defilement, sacrifice for sin.”91 This is the same Greek word we saw earlier in LXX Psalm 129, the Hebrew basis for which was סְלִיחָה (“forgiveness”). The two most common contenders for the correct translation of this text are “propitiation” and “expiation.”

Propitiation makes God the object of the action; God is propitiated. The word refers to “something done to win the favor of a, usually angry, god, spirit, or person.”92 While many Reformed theologians would prefer this understanding of the term, it is interesting that it is not exclusive to them.93

“Expiation,” on the other hand, means “cancellation or dismissal.” As Yarbrough goes on to note, “God simply waives the threatened penalty for transgressions.”94 In expiation, God is the subject of the action. Smalley notes that expiation makes sense of the Hebrew סְלִיחָה in passages like Psalm 130.95 One could almost translate it “He is the basis for the forgiveness of our sins.” Christ is our advocate, and one of the ways he advocates for us is by forgiving our sins.

But not only for ours, but also for the whole world (οὐ περὶ τῶν ἡμετέρων δὲ μόνον ἀλλὰ καὶ περὶ ὅλου τοῦ κόσμου). This phrase declares the scope of Christ’s work. Christ has not merely forgiven the sins of Christians in communion with the Church. He has forgiven the sins of the whole world. But John does not write this to teach universalism.96 Rather, this is a challenge both to those still in John’s Church and to those who have departed.

To those who remained in the flock, John says, “Christ is willing to forgive them. He forgave you. Do not withhold forgiveness from them!”97 To those who left, John says, “It does not matter where you go, Christ’s sacrifice was for the whole world. He is the God of the whole world, not confined to one region or another. Return to the Church!”98

Exposition and Application

Community. It’s a buzzword in Christian circles. We have community groups, community outreach, community presence. John would have no clue what these terms mean.

John’s vision of community is God-centered. God’s people gather to hear God, to confess where they fail to live like God, and to be challenged to love like God. They aren’t learning about God—they’re experiencing God.

John’s initial doctrinal declaration—what he’d been building to since 1:1—is “God is light.” Light illuminates what was previously hidden. Light provides safety. Light provides comfort.99 For John’s community—and for us today—the way to know if we are walking with God is if we seek the light. Fleeing from God’s illumination (the word of life [1:1]; Psalm 119:105) results in damnation.

John gives us three marks to determine if we belong to the Church.

1) Do we seek God actively, or do we flee from what his message reveals about us? Don’t take this question to your unbelieving neighbors! God is asking you. Confess your deficiency in this area to God—and a trusted friend—and return to fellowship!

2) Do we confess our sins, or do we claim sin isn’t a problem for us? The light of God will reveal all the places we are falling short, especially if we view sin as breaches in a relationship and not failure to follow a bunch of rules.100 You have not yet arrived, so be humble enough to allow the light of God to reveal the places in your heart where you need to repent. Don’t wait! And make sure to confess to a trusted friend as well.

3) Do we embrace the solution for our sin, or do we instead claim that our actions do not qualify as sin? The light of God is supposed to illuminate our sin and draw us back to him, since he is our only hope for freedom and cleansing from sin. Failure to confess our sin breaks not only our vertical fellowship with God, but also our horizontal fellowship with one another. It downplays Christ’s role as our advocate and expiation and leads to hypocrisy or despair.

All three of these marks emphasize the gospel. The gospel is the solution to both hypocrisy and despair. All three marks refer back to Christ’s work on the cross on our behalf for sin. While his work is available to the whole world, the only ones who benefit are those in the community. So there’s no reason to treat those outside the community as if they are bound by the same expectations as those within the community. (See further below on Gospel and Great Commission.)

The Christian, John says, is marked by taking sin seriously, by confessing both that it is a reality in his or her life and that he or she knows the One who is able to deal with it. But this naturally leads to the question: “If I’m still struggling with sin—if I can never say, ‘I’ve made it’—then how do I know I have fellowship with God? Especially if I struggle with the same things that people out there struggle with?” It’s a great question. John answers it next time.

Saint Augustine Assessment

This section of the post is for paid subscribers only. For details on this section, click here.

Gospel Plea

“God is light.” So come to the light. It’s as easy as that. You don’t need to clean yourself up first. No, Jesus will do that for you as you press on in fellowship with him. But you do need to come to him.

As John wrote elsewhere, “Everyone who practices worthlessness hates the light and will not come to the light, in order that his or her deeds might not be exposed” (John 3:20). Does your desire for God exceed your desire to keep your sin from being exposed? Come to him! Come to the light!

Jesus came on the scene preaching, “Repent and believe!” (Mark 1:15). Turning to the light and turning away from the dark is simultaneously belief and repentance. Come to the light!

Great Commandment Plea

If all Christians sin, then there should be no space for pride or arrogance in the heart of a Christian. If the answer to all of our sin is the same, then, again—because no one can claim exclusive access—there is no room for pride or arrogance in the heart of a Christian.

This makes the Great Commandment plea simple. Walk with one another through confession, struggle, victory, relapse, confession. Keep showing up. Keep modeling the love, faithfulness, and righteousness of Christ by refusing to give up on one another. This is the type of judgment-free, non-hypocritical community the world needs to see. They will know us by our love!

Reflection Questions

- How do you make sense of John’s claim, “God is light”?

- What do you think of the order of salvation I laid out? How would you alter it? Why?

Openness to God –> Closeness to God –> Fellowship with God’s Children –> Conviction of Sin –> Cleansing from Sin –> Victory over Sin

- Are you more likely to claim sin does not affect you or that certain actions are not actually sin?

- What is the proper approach if we are in a time of public confession and someone confesses to illegal activity?

- How do the implications of “[Jesus] is the expiation … for the sins of the whole world” personally apply to you? Who does it bring to mind?

Thanks for reading!

In this with you!

While I am committed to providing theological reflections at no charge, your paid subscription makes my writing possible and helps me reach more people with the gospel of God’s love. If you’re not currently a paid supporter, please consider becoming a supporter today.

Buy Me a Coffee

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateNotes and References

- Mark Dever, Nine Marks of a Healthy Church: New Expanded Edition (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2004). A better read is Timothy George and John Woodbridge, The Mark of Jesus: Loving in a Way the World can See (Chicago, IL: Moody, 2005). ↩︎

- A count of references reveals ~400 in the Scripture Index (Dever, Nine Marks, 283–287). Nine of these are from 1 John, though none are mentioned prior to 3:2, besides two references to the book as a whole in the Preface and Introduction. Five of the remaining seven references are pulled, with no thought for context and no textual discussion, to support various of Dever’s marks (two of which—3:18; 4:20—are used to support Church Membership). It’s beyond the scope of this chapter, but his mark on Church Discipline probably militates against the biblical mark John envisions in this text, though he does write: “Biblical church discipline is simple obedience to God and a simple confession that we need help” (p. 192, emphasis added). Besides a passing reference to “confessing sin” (likely alluding to 1 John 1:9) in a narrative on pages 195 – 198, these are the only references to confession in the whole book (at least according to his Index). But as the text we are considering today shows, confession is critical to understanding 1 John. ↩︎

- See James K. Lee, Augustine and the Mystery of the Church (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2017), 45–52. He later writes, “By bearing with the wicked, the members of the church are configured to the patience of God. This purification occurs in the midst of a community in constant transformation, and so the church is a dynamic reality, not a static one. Each person must undergo the transformation from Babylon to Jerusalem in the context of a fellowship of believers, with some of its members, namely, the saints and angels, already sharing in the perfect union of charity in heaven” (p. 89). ↩︎

- I read ἀγγελία rather than επαγγελια. ↩︎

- I do not read δε here, since it is absent in 1:9 and 2:1 as well and there is no variant witnessing its addition at any point. ↩︎

- I do not read Χριστοῦ here, since this addition can easily be explained by trying to make it parallel with 1:3 and 2:1. ↩︎

- I read καθαρίζω as a Present, Active, Indicative. This makes much more sense of the context; it is not a future reality that will comfort John’s readers, but a present reality they need to be reminded of. ↩︎

- I do not insert του θεου here. Only two manuscripts witness this reading, and it is easily understood as an explanatory gloss. ↩︎

- I do not insert the possessive ημων here. The dative ἡμῖν that is present in the text can be understood as carrying the possessive nuance (see Wallace, Greek Grammar, 149–151). ↩︎

- I read καθαρίζω as an Aorist, Active, Subjunctive. This makes much more sense of the context; it is not a future reality that will comfort John’s readers, but a present possibility they need to avail themselves of. ↩︎

- I read ἁμαρτάνω as a Perfect, Active, Indicative. The support for the possibility of an Aorist is flimsy. ↩︎

- I read ἁμαρτάνω as an Aorist, Active, Subjunctive. The support for the Present is just as flimsy as the support for the Aorist above. ↩︎

- I read μόνος as an adverb because otherwise it does not fit in the “not only … but also” scheme (see Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 27). ↩︎

- This includes verbs that are parsed as first-person plurals that lack an emphatic pronominal subject. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 194. He draws attention to John 16:13, 14, 15. The only other usages of this verb in John’s writings are John 4:25 (the Samaritan woman talking about Messiah announcing all things); John 5:15 (the former cripple announces Jesus’ identity to the Jews); and here. ↩︎

- Carson, “John, Letters of,” 402–403. Admittedly, he only connects it to 2:27, but if it is there, it is likely also in the background of other portions of 1 John as well. ↩︎

- In English translations, this is Jeremiah 31:33b–34. ↩︎

- E.g., G. K. Beale, Handbook on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament: Exegesis and Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 31. ↩︎

- Carson, “John, Letters of,” 403. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 184. He refers to Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John XIII–XXI, AB (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970), 1140. ↩︎

- Another crucial reality in 1 John on which these depend is found in 4:8, 16: “God is love,” grammatically identical. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 191. On page 224, he writes, “1:5 serves as a transition from the Prologue to Part One by proclaiming the basic gospel message the author wishes to defend.” ↩︎

- Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, “Cosmic Microwave Background,” Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.cfa.harvard.edu/research/topic/cosmic-microwave-background: “For the first 380,000 years or so after the Big Bang, the entire universe was a hot soup of particles and photons, too dense for light to travel very far.” Photons are light particles, and while maybe not always visible light, the fact remains that light is from the beginning, no matter how you want to explain that beginning. ↩︎

- He uses a double negative to emphasize the impossibility (Culy, I, II, III John, 13). ↩︎

- Lieu, I, II, III John, 50. ↩︎

- Eternal in the sense of quality more than quantity. Life is from the beginning (1:1), and God created light in the beginning (Genesis 1:1–3). ↩︎

- Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 16. Even Augustine (at least in Homilies 1.4–5, pp. 24–26) never refers to God’s essence as light. ↩︎

- See Anselm of Canterbury, Monologion 49–61 (pp. 60–67). Page numbers are based on Anselm of Canterbury, The Major Works, ed. Brian Davies and G. R. Evans, Oxford World’s Classics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008). ↩︎

- Lieu, I, II, III John, 51. ↩︎

- Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 64–65. ↩︎

- Wallace, Greek Grammar, 696. Emphasis in original. ↩︎

- Akin, 1, 2, 3 John, 72. This avoids Wallace’s discussion about whether it indicates a reality or a hypothetical situation (Greek Grammar, 696–697). However, given 1 John 2:19, it would appear that it was a reality in the community, and John is attempting to prevent further splintering. Jobes explains the case as follows: “This third class conditional is used to present a hypothetical situation that may or may not be in direct reference to those who left the Johannine church(es) under less than amiable circumstances” (1, 2, & 3 John, 68). ↩︎

- Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 18; Brown, The Epistles of John, 197. ↩︎

- Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 22; Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 67. ↩︎

- Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 22. ↩︎

- The perfect in 1:10 and the two aorists in 2:1 will be discussed in the exegesis that follows. ↩︎

- Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 19. ↩︎

- Yarbrough, 1–3 John, 46. ↩︎

- I guess one could argue this is still a test. I did title this post “the Marks of a Christian” after all, but I would note that whereas the “tests” view emphasizes my standing with God, this perspective is more concerned with ensuring that no one falls short of God’s grace (cf. Hebrews 12:15; footnote 3 above). ↩︎

- Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 20 n. 21: The construction here can be understood as “the inclusion of a person in a thing … and of the inclusion of a thing in a person.” ↩︎

- John Behr, The Way to Nicaea, The Formation of Christian Theology (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2001), 57. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 200. ↩︎

- If Christ is to be emphasized as the one John witnessed as an example of walking in the light, it might serve as a parallel to the idea we find later in 4:17, “We are as he is in this world,” similar to the idea present in John 1:18. Brown (The Epistles of John, 201), speaking of the difference between “God is light” (1:5) and “He is in the light” (1:7), explains, “One portrays God’s being as the basis for Christian experience; the other portrays Him as the model for Christian behavior.” ↩︎

- Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 19. ↩︎

- Strecker, The Johannine Letters, 30. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 1.5, p. 26. ↩︎

- Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 20. ↩︎

- One thinks of Acts 9:4–5. ↩︎

- Akin does a disservice to the text when he interprets the passage according to a very minor variant that reads “αὐτοῦ, ‘him,’ i.e., fellowship with God rather than fellowship with one another,” as discussed in Z. C. Hodges, “Fellowship and Confession in 1 John 1:5–10.” Bibliotheca Sacra 129 (1972): 48–60. The apparatus of NA28 does not even draw attention to this variant. But other than a footnote arguing for a nuanced understanding of Hodges’ argument, Akin just assumes 1:6 and 1:7 read identically. See Akin, 1, 2, 3 John, 72 n. 124. Yarbrough, 1–3 John, 67: “Hardly better attested [than the previous variant he discussed on 1:7] is μετ᾿ αὐτοῦ instead of μετ᾿ ἀλλήλων, and the latter reading is surely original.” ↩︎

- Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 70. ↩︎

- Brown compares this teaching to John 13:8, 10, and especially 14, where Jesus said, “If, then, I—the Lord and Teacher—washed your feet, then you must also wash one another’s feet” (The Epistles of John, 239). ↩︎

- Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 28; Akin, 1, 2, 3 John, 74; Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 21; Yarbrough, 1–3 John, 60; Strecker, The Johannine Letters, 31; Brown specifically refers to the “guilt of sin” (The Epistles of John, 234); Luther understands the claim as referring to those who are presumptuous (LW 30:229). ↩︎

- Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 70–71. The number of directions in which one might expound this quote could be a book in and of itself. ↩︎

- Strecker, The Johannine Letters, 31. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 1.6, p. 26. ↩︎

- Contra Yarbrough, 1–3 John, 63 n. 13, who calls this the “semantic root fallacy” (see D. A. Carson, Exegetical Fallacies, second edition [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1996], 28–33), since “In few if any NT passages where ὁμολογέω appears can one make sense of a text by using the translation ‘to say the same thing as.’” I would hope that the exegesis provided shows that this is exactly what the word means in this context. ↩︎

- Akin, 1, 2, 3 John, 74. Akin has a footnote in this sentence that argues against public confession. But his reasoning for this footnote is based on his flawed understanding as described in footnote 46 above. Lieu writes, “The plural ‘we’ belongs to the debating style of the letter, but may also indicate a public, corporate context for such confession; the formulaic phrasing that follows in the assurance of forgiveness also suggests this” (I, II, III John, 58). In Lutheran churches, communion is given with the vocal promise, “Your sins are forgiven.” ↩︎

- Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 31. Emphasis in original. ↩︎

- Strecker, The Johannine Letters, 32. ↩︎

- Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 71. ↩︎

- Moisés Silva, Biblical Words and Their Meaning: An Introduction to Lexical Semantics (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994), 28: “We learn much more about the doctrine of sin by John’s statement, ‘Sin is the transgression of the law,’ than by a word-study of ἁμαρτία.” In what follows, I trust that this shows. ↩︎

- Louw and Nida, Greek-English Lexicon, 425. ↩︎

- I owe this observation to Anthony Tyrrell Hanson, “Elements of a Baptismal Liturgy in Titus,” Studies in the Pastoral Epistles (London: S.P.C.K., 1968), 93–96. ↩︎

- I owe this observation to Lieu, I, II, III John, 58. ↩︎

- I will provide a translation on 2:2, which will be able to be retroactively applied here, but for now, it will stay hilasmos. ↩︎

- Lieu, I, II, III John, 58. ↩︎

- Lieu, I, II, III John, 58. ↩︎

- It is worth noting that David J. A. Clines, ed., The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew, vol. 5 (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 749, lists “To clean” as a possible definition of the verb נקה. ↩︎

- Lieu also notes this translation in the LXX (I, II, III John, 58). ↩︎

- Wallace, Greek Grammar, 577. Just because the emphasis is on the past, it does not mean it says nothing about the present state. ↩︎

- See Lieu, I, II, III John, 59: “The very fact of divine forgiveness demonstrates the reality of sin, and since God’s character both defines sin and inspires the forgiveness that God offers, then any denial of sin calls into question God’s fidelity and truthfulness, treats God as a liar.” ↩︎

- Evidence-based apologetics. The kind Jesus taught (John 13:35). ↩︎

- John H. Walton and D. Brent Sandy, The Lost World of Scripture: Ancient Literary Culture and Biblical Authority (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2013), 156: “In many verses ‘message’ is an appropriate gloss for logos, for the context makes clear that oral texts were in view.” ↩︎

- Strecker, The Johannine Letters, 33. He draws attention to Eichholz and Käsemann who claim that 1 John is the first church writing to develop the motif “simul justus et peccator” (n. 32). ↩︎

- Akin draws attention to 5:16 in his discussion of 2:1–2, though he does not connect it to the schism as I do (1, 2, 3 John, 82). ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 242. ↩︎

- Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 22 n. 35. ↩︎

- Augustine, On Man’s Perfection in Righteousness 18.39; 21.44, cited in Luther, LW 30:228. ↩︎

- Luther, LW 30:235. The textual variants on αμαρτανω between 1:10–2:1 make it clear what he means. Christians have struggled with this text from the beginning. ↩︎

- Yarbrough, 1–3 John, 74 fig. 4. His x-axis is “faith,” his y-axis is “righteousness,” and his z-axis is “love.” The danger of this perspective is that it declares everyone outside of the right “octant” to be unsaved, which is not the point of 1 John. This is a holdover from the “tests” perspective of 1 John that I am trying to avoid in this commentary. Yarbrough only mentions test(s) nine times (besides a reference to “tests of time”), and six of them occur in his discussion of 4:1–3 (pp. 46 n. 2, 192, 205, 220 [2x], 223 [2x], 224 [2x]), so he is by no means intending to emphasize the “test” perspective. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 215. ↩︎

- Contra Akin, 1, 2, 3 John, 78: “In context, ‘anyone’ has to be ‘anyone [of us],’ that is, John or any of the believing community.” The verb here is an aorist, and it is incorrect to make this tense automatically refer to one-time action (see Mathewson and Emig, Intermediate Greek Grammar, 123). However, if John is referring to the exodus he describes in 2:19, it would be a one-time action, that, admittedly, would play out in continued sin due to continued lack of love/fellowship (whether an aorist of present-time action, extended action, or repeated action; see Mathewson and Emig, Intermediate Greek Grammar, 120–124). ↩︎

- See Augustine Assessment below for his perspective on this idea. The Catholic Church today would not take as strict of a position (see Avery Dulles, Models of the Church [Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974], 120–121). ↩︎

- Bultmann, The Johannine Epistles, 22. ↩︎

- Luther, LW 30:236. ↩︎

- Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 37–38. ↩︎

- Referring to God/Jesus: 1:9a; 2:1, 29a; 3:7. Referring to us: 1:9b (cleansed from the opposite); 2:29b; 3:7 [2x]. Other references: 3:10, 12; 5:17. Righteousness is real, and chalking it up to something “credited to our account” has done a disservice to Christendom for 500 years now. ↩︎

- Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 36. ↩︎

- We have already noted references to Jesus as our model (see above on 1:7), so this should not be a surprise, especially given the repeated references to God/Jesus as our model for righteousness (see footnote 87 above). So this understanding gives added meaning to Matthew 18:15–17 and the pericope prior: “The Good Shepherd” (Matthew 18:10–14). When Matthew 18:17 says to treat someone like “an unbeliever or a tax collector,” it means to pursue their soul like a shepherd looking for a lost sheep. And who knows: Perhaps Jesus’ advocacy can also take the form of his people living like this toward others, laying down their lives in the process? John does go on to say in 1 John 4:17 that “We are as he is in the world.” ↩︎

- It should be noted that 1 John 3:16 and 4:9–10 are spoken in the same breath as propitiation/self-giving death. ↩︎

- Brown, The Epistles of John, 218. ↩︎

- Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 79. ↩︎

- See MacArthur, 1–3 John, 46; for an Arminian scholar who takes this perspective, see I. Howard Marshall, The Epistles of John, NICNT (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1978), 117. ↩︎

- Yarbrough, 1–3 John, 78. ↩︎

- Smalley, 1, 2, 3 John, 39. ↩︎

- See Calvin, Commentaries on the Catholic Epistles, 173. ↩︎

- Cf. Matthew 18:21–35. ↩︎

- For this idea, see Jobes, 1, 2, & 3 John, 80; cf. Augustine, Homilies 1.8, p. 29–30, who uses this passage to convince the Donatists to return to the Catholic Church: “See, you have the Church everywhere in the world; don’t follow false righteous-makers and true off-cutters. Be upon that mountain which has filled the whole earth.” ↩︎

- Παράκλητος is often translated “Comforter.” ↩︎

- Jesus’ explanation of the Greatest Commandment (Mark 12:29–31) confirms the validity of this perspective on sin. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 1.6, pp. 26–27. ↩︎

- Ramsey, ed., “Footnote 10,” in Homilies, 27. He refers to ST I-II, Q88, A4. ↩︎

- F. L. Cross and Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds., “mortal sin,” The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 1124. ↩︎

- Augustine, Homilies 1.8, pp. 28–29. Emphasis in original. ↩︎

- See Saint Augustine, “Psalm Against the Party of Donatus,” The Donatist Controversy I, ed. Boniface Ramsey, Maureen Tilley, and David G. Hunter (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 2019), 29–46. “Arrogant” or related forms occur in sections B, D, and Q of this alphabetic song: They’re people who are very arrogant, who say that they are righteous” (B, p. 33). ↩︎

- Augustine, “Psalm,” sec. V, p. 46. Emphasis added. ↩︎

- See Tilley, The Bible in Christian North Africa, 151–162. ↩︎

One thought on “The Marks of a Christian | 1 John 1:5–2:2”